The Man Who Died First

Thank you to everyone who voted in my poll last week. It looks like most people would like to see my fiction and non-fiction posts separated in some way, so I will be looking into getting that set up in the new year. This will be my last post of 2023, however. I am working on another project (I’m trying to write season two of my audio drama Experiment 31E), and I have found it difficult to juggle both that and this newsletter, so I will be taking some time off until I finish that other project. I hope to be back on a regular posting schedule again in January or February. Have a great rest of the year and happy holidays!

On December 10, 1826—197 years ago—a young boy named John Torrington was baptized in Manchester, England. We don’t know his actual birthdate. He may have been born several weeks earlier in 1826, along with his sister, Esther, who was baptized the same day as him. Or he may have been born late in 1825, as some records suggest. He came from a working-class family, one where not everyone could read or write, and there are few records of him at all. His father was William, a coachman, and his mother was Sarah, whose maiden name, Shaw, became John’s middle name. He was an ordinary boy, one of many who were baptized that day. His name sits at the bottom of the page of the parish baptism registry, easily missed, easily forgotten.

His name wasn't forgotten, though. There are those who still remember him to this day, but not because of what he did in life. We remember him because he died.

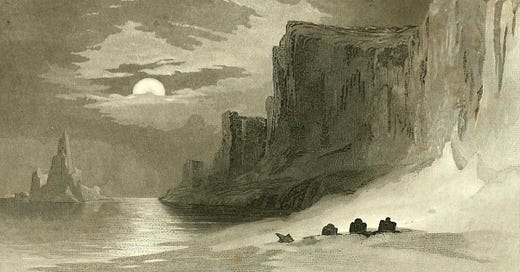

John Torrington was the first fatality of the Franklin Expedition. Led by Sir John Franklin, the expedition had set out from England in 1845 to find the last link of the Northwest Passage through the Arctic. Most of the passage had already been discovered, and the expedition was supplied with three years’ worth of food, steam engines, and reinforced ships. Everyone assumed they would be home in a year or two, the passage finally conquered.

No one survived.

Exactly what happened to the Franklin Expedition is still not fully understood, and because of that mystery, many people are obsessed with trying to find out what happened, myself included. The Franklin Expedition has become one of my special interests over the years—something my autistic mind obsesses over to no end—but while I am captivated by the mystery of what happened to the expedition, there is another mystery that fascinates me even more:

Who was John Torrington?

That is a question I have spent the last several years trying to answer, but sadly with few concrete facts to show for it. I have written extensively about my attempts at researching him—you can find all my posts on my old blog (and admittedly, this post here has been cobbled together from a couple of my previous ones)—but for all the thousands of words I’ve spent on him, the only details of his life I can be sure of can be summarized in a couple of sentences: He was baptized in Manchester in 1826, with his sister, Esther. He worked as a leading stoker (someone who tends to a coal-powered steam engine) on the Franklin Expedition and died within the first several months of the expedition in 1846. And that’s about it.

You may be asking why exactly am I so obsessed with a dead Victorian sailor, and that is a good question. I have tried pinpointing just what it is that has drawn me to him over the years, and it is a complicated thing that goes back to my childhood. But before I delve into that, I feel I should explain a little bit more about the Franklin Expedition—and in particular, the special something that made John Torrington a name some people can never forget.

Torrington had the dubious honor of being the first of 129 men to die—an omen for those of us looking back nearly two hundred years after the fact. Rather than being buried at sea, like many sailors usually were, he was buried on Beechey Island, a small strip of land in the Arctic. The expedition had sheltered on Beechey during their first winter, and three men died during that time, all of them buried in the frozen permafrost. Torrington died on January 1, 1846, at just twenty years old. John Hartnell died a few days later, on January 4, and William Braine followed a few months afterward on April 3.

When the expedition failed to return home after a few years, rescue missions tried to find them. They discovered the expedition’s winter quarters—and the graves.

The wooden headboards of Torrington, Hartnell, and Braine, painted an ominous black, were not a good sign for the rescue crews. Previous expeditions to the Arctic had lost crewmembers, but losing three men in the first winter was unusual. As the years went by and the rest of Franklin’s crew were still missing, it became apparent there were no survivors. Skeletons, scattered relics, and a brief message placed in a cairn of stones would reveal that the ships had become stuck in the ice for two years and the men had tried to walk across the barren land to safety. Before their trek, however, they had lost a significant number of men already, including Franklin himself.

The question of how the expedition met its doom has plagued rescue missions, scholars, and armchair enthusiasts for nearly two centuries. One man, anthropologist Owen Beattie, thought the answer could be found with the men buried on Beechey.

In the early 1980s, Beattie had found bones from members of the Franklin Expedition on King William Island, where most of the crew is believed to have met their demise. These bones contained high levels of lead. Beattie theorized that lead poisoning, caused by the lead-soldered cans of food brought along as provisions, may have contributed to the expedition’s demise, but to prove it he would need to find soft tissue samples. In 1984, he led a team to Beechey Island. He hoped the permafrost had preserved the three men buried there so he could extract tissue to prove his theory. He started with the first man to die, John Torrington.

When Torrington was exhumed, Beattie discovered the permafrost had indeed preserved the body—in fact, it had preserved it so well that Torrington appeared as if he had only just died. Torrington wore a blue striped shirt, gray pants, and a polka-dotted kerchief wrapped under his jaw. His blue eyes were half open, staring back at the scientists as they melted the ice encasing him. Although his lips had curled into a grimace due to the mummification process and a navy blue cloth covering his face had stained his forehead, he could have otherwise been mistaken for someone who had been sleeping.

An autopsy showed that Torrington had been very sick at the time of his death. His lungs were blackened—a combination of living in the heavily polluted city of Manchester, working as a stoker, and smoking. He had signs of previous lung infections and possibly emphysema, and he most likely had tuberculosis. The actual cause of death could not be determined, but it was suggested that pneumonia, brought about by tuberculosis, was the culprit. Torrington did have high levels of lead in his hair and bones, which Beattie used as proof of his theory, but many subsequent studies have poked holes in his research. For one thing, lead levels were high for many people living in England during the Victorian period. Torrington especially would have come into contact with a significant amount of lead prior to the expedition because coal ash contains lead, and working as a stoker and living in an industrial city like Manchester, where factories constantly spewed coal dust into the air, would have brought him into frequent contact with it.

Prior to the autopsy, Beattie took pictures of Torrington’s preserved remains, pictures that were shared around the world by newspapers, magazines, and television news programs. It was these images of Torrington that catapulted him to a kind of macabre fame. Those photos inspired songs, books, artwork, and even an upcoming movie. And those pictures both intrigued and terrified a little undiagnosed autistic girl in Virginia.

(Note: I won’t be including the pictures here in this post since they are photographs of a corpse and some people may find them disturbing. A quick Google of Torrington’s name, though, will bring them up if anyone is curious—but be warned, they are pretty creepy.)

When I was about seven or eight, my older brother brought home a copy of Beattie’s book Buried in Ice from school, where he was learning about the Franklin Expedition. He of course shared the pictures in the book with me and our older sister because he thought they were creepy and that’s what you do when you’re a kid, you try to scare your siblings. And scared I was. Torrington looked undead, like he might lumber out of his coffin at any moment and attack. For years he was the monster in my closet, the boogeyman under the bed, the thing in the dark I closed my eyes to hide myself from.

Remarkably, despite being terrified of Torrington, I somehow became obsessed with mummies as a child, an obsession that continues to this day. From a young age, I would borrow books from the library about them and marvel over pictures of Tollund Man, Ötzi, and the Qilakitsoq mummies of Greenland.

But not John Torrington.

Whenever I flipped through a book about mummies, if I encountered a picture of Torrington, I would slam my hand over the page to cover it. Other mummies creeped me out too, but never to the same degree as Torrington. And yet, I still felt compelled to peek, even after covering the page. I would regret it immediately, but there was something that made me want to look even though I knew it would give me nightmares.

Over the years, Torrington found his way into several stories of mine, in some form or another. Many of my early works turned him into a ridiculous comic relief character as a way to cope with my fear of him. But as I grew older, something began to change in how I saw him, and one story idea in particular inspired me to start poking at the mystery of who Torrington was.

I wanted to include him as a fully realized character in a novel, and I felt that I should research him so I could portray him accurately. I began reading everything I could about the Franklin Expedition, and I delved into historical records to find out more about him. My childhood nightmares lingered at first, but my research started to shift those in strange ways. I had always seen Torrington as this ancient, towering monster, but then I discovered he was only twenty when he died and stood at only five-foot-four. I’m older than him. I’m taller than him. His desiccated body weighed less than ninety pounds, which I definitely weigh more than. Basically, if he came charging out of the closet, I could take him.

But what really drew me in was realizing that we know so little about him. Even Owen Beattie’s research had failed to turn up anything more than basic information about Torrington’s life. We know more about how he died than how he lived. It was frustrating—I could look at a picture of his face, frozen in time, but I couldn’t reach back into the past to ask him about himself. I’ve known about him almost my whole life, with him skulking in a corner of my brain, stepping out of the shadows every now and then, but I didn’t really know who he was as a person.

The Franklin Expedition can drive people mad with the mystery of what happened to the men after they entered the Arctic, but suddenly I became obsessed with knowing what had happened before the expedition. Who was John Torrington? Who was this guy that has occupied my dreams and nightmares, who has taken up permanent residence in my mind ever since I first laid eyes on him? Who was this young man who has somehow been a part of my life for so long, but whom I know so little about?

I wish I had a proper answer to those questions, but even after all my attempts at research, Torrington’s life is still very much unknown. While most people focus on the mystery of the lost expedition or gawk over the photos of Torrington’s mummified body, it is often forgotten that the man staring back from those pictures was a human being. We know so very little about him, the bare bones of his life having been pieced together through a scant few records and the headboard of his grave. What little can be gleaned is that he died young, far from home, and that may be the only legacy he is remembered by. But he had a life before then. He had family back home waiting for him. Maybe he even had dreams of a life better than the lot of a lowly stoker. One of the few things we know for sure, however, was that nearly two centuries ago he was baptized, his parents taking him to church for the sacrament alongside his sister. He was loved, he was cared for. And for that, too, he should be remembered.

Thank you for reading Ramblings from the Moon! All posts are currently free, but if you would like to make a donation to help fund my writing, you can do so at my Ko-fi account. Thank you!